What Type of Plastic Can Be Recycled Explained

Share

When it comes to plastics, the two heavy hitters in most recycling programs are PET (#1) and HDPE (#2). You’ll recognize PET as the clear plastic used for water and soda bottles, while HDPE is the sturdy, often opaque material used for milk jugs and laundry detergent containers.

These two are the bread and butter of plastic recycling. Why? Because there's a strong, consistent market for them, and they are relatively easy for facilities to sort and process. While you’ll see recycling symbols on all sorts of plastics, #1 and #2 are the ones most universally accepted in curbside bins.

Your Guide to Commonly Recycled Plastics

Here’s one of the biggest myths in recycling: that the chasing arrows symbol means something is automatically recyclable. It doesn't.

Think of that little number as an ingredient label, not a seal of approval. It just tells you what kind of plastic resin the item is made from. A standard water bottle (PET #1) is like a letter with a clear address and a stamp—the postal system knows exactly what to do with it. But a foam takeout container (Polystyrene #6) is like a glitter bomb in an envelope; it's a contaminant that gums up the works and is almost always rejected.

To really make a difference, you need to focus on the recycling "all-stars"—the plastics that facilities are actually set up to handle and that manufacturers want to buy back.

The Most Wanted Recyclables

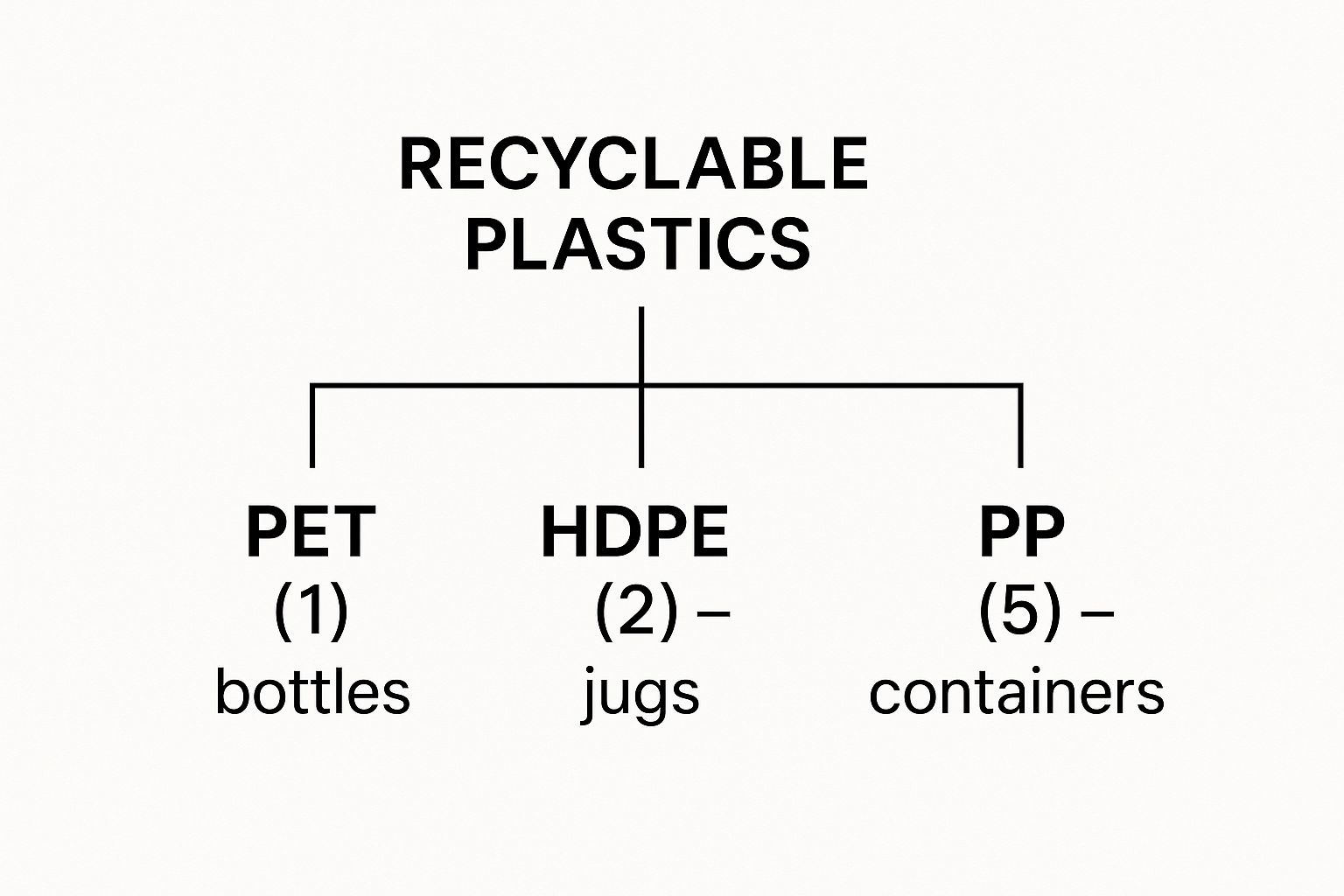

Globally, only a handful of plastic types are recycled with any consistency. The big three are resin codes 1 (PET), 2 (HDPE), and sometimes 5 (PP). High-Density Polyethylene (#2) is a particular favorite in the recycling world because it's rigid and durable, making it ideal for those milk jugs and cleaning supply bottles.

On the flip side, plastics like PVC (#3) and Polystyrene (#6) are rarely accepted in curbside programs. They're often chemically complex, can release harmful toxins when melted, and pose significant contamination risks to other, more valuable plastics. You can dive deeper into why recycling rates for some plastics have stalled to understand the economic and technical hurdles.

To make things easier, here's a quick look at the plastics that have the best shot at being recycled.

Frequently Recycled Plastics at a Glance

This table breaks down the most common plastics you'll encounter and whether they are typically accepted in local recycling programs.

| Resin Code | Plastic Type | Common Examples | General Recyclability |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | PET | Water bottles, soda bottles, peanut butter jars | Widely Recycled |

| #2 | HDPE | Milk jugs, detergent bottles, shampoo bottles | Widely Recycled |

| #5 | PP | Yogurt tubs, margarine containers, some bottle caps | Often Recycled (Check locally) |

As you can see, focusing on #1 and #2 plastics is your safest bet, with #5 being a "maybe" depending on where you live.

The key takeaway is simple: not all plastics are created equal in the eyes of a recycling facility. Prioritizing clean #1, #2, and sometimes #5 plastics gives your recycling efforts the best chance of success.

Getting a handle on these differences is the first big step. It helps you move from just hoping something gets recycled to making sure what you put in the bin actually has a chance at a second life.

Decoding The 7 Plastic Recycling Codes

Ever wonder about that little number stamped on the bottom of a plastic container? That symbol, with the number inside the chasing arrows, is called a Resin Identification Code (RIC). It's a common misconception that this symbol means the item is automatically recyclable. In reality, it was created by the plastics industry simply to help sorting facilities identify the type of plastic resin they're dealing with.

Think of it as a plastic's ID card, not a recycling guarantee. Learning to read these codes is the first step in moving from a hopeful recycler to an effective one, because it tells you what you’re holding and helps you figure out if it can even be recycled in your town.

This quick visual guide is your key to recognizing the seven main families of plastic.

To make sense of it all, I've put together a simple cheat sheet. This table breaks down each code, what it's called, where you'll find it, and its current recycling status.

The Complete Plastic Recycling Cheat Sheet

| Code | Abbreviation | Full Name | Common Products | Recycling Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | PET or PETE | Polyethylene Terephthalate | Soda bottles, water bottles, peanut butter jars, salad dressing containers | Widely Recycled. High demand for this material. |

| #2 | HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene | Milk jugs, laundry detergent bottles, shampoo bottles, cleaning supply containers | Widely Recycled. Another valuable plastic with a strong market. |

| #3 | PVC or V | Polyvinyl Chloride | Pipes, vinyl siding, some shrink wrap, clear food packaging, window frames | Rarely Recycled. Can release toxins when processed and contaminates other plastics. |

| #4 | LDPE | Low-Density Polyethylene | Plastic shopping bags, bread bags, shrink wrap, bubble wrap | Sometimes Recycled. Not in curbside bins. Must go to special store drop-off locations. |

| #5 | PP | Polypropylene | Yogurt tubs, margarine containers, medicine bottles, some food takeout containers | Sometimes Recycled. Acceptance is growing but varies by location. Check local rules. |

| #6 | PS | Polystyrene | Styrofoam cups, takeout containers, packing peanuts, meat trays, egg cartons | Rarely Recycled. Lightweight and bulky, making it economically difficult to process. |

| #7 | OTHER | Miscellaneous Plastics | Multi-layer plastics, bioplastics, polycarbonate (water cooler jugs) | Almost Never Recycled. A catch-all category that is too mixed to sort effectively. |

Now that you have the overview, let's break these down into three simple groups: the "Yes," the "Maybe," and the "Almost Never." This will help you quickly sort your plastics without having to memorize the whole chart.

The Easy Wins: Widely Recycled Plastics

Let's start with the recycling all-stars. These are the plastics that most curbside programs are built to handle because they have strong, stable markets.

-

#1 PET (Polyethylene Terephthalate): This is the clear, lightweight plastic that makes up things like water and soda bottles, or the jar your peanut butter comes in. It’s a hot commodity in the recycling world and is often turned right back into new bottles or spun into polyester fiber for clothes and carpets.

-

#2 HDPE (High-Density Polyethylene): A bit tougher and usually opaque, HDPE is the stuff of milk jugs, laundry detergent bottles, and shampoo containers. Just like PET, there's a robust market for recycled HDPE, which gets a second life as new containers, plastic lumber, and even patio furniture.

Focusing on these two plastics is the surest way to know your efforts aren't going to waste.

The "Maybe" Pile: It Depends on Where You Live

Next up are the plastics that live in a bit of a gray area. Whether you can recycle them is completely dependent on your local facility’s equipment and whether there's a buyer for the material.

-

#4 LDPE (Low-Density Polyethylene): This is the soft, flexible plastic used for grocery bags, bread bags, and the film that wraps a case of water bottles. While LDPE is technically recyclable, it absolutely cannot go in your curbside bin. These films are notorious for tangling in sorting machinery, causing major shutdowns. They must be taken to dedicated store drop-off bins.

-

#5 PP (Polypropylene): Known for being heat-resistant, you’ll find PP in yogurt cups, margarine tubs, and some medicine bottles. Its recycling fate is improving, but it's not a universal "yes" like #1 and #2 plastics are. It's crucial to check your local program's guidelines for this one. Even everyday items like plastic lids can be made from PP, so checking the code is key.

The real barrier for these "maybe" plastics isn't a lack of value—it's logistics. The cost and technical difficulty of collecting, separating, and cleaning #4 and #5 plastics are just too high for many recycling programs to justify.

The Tough Cases: Almost Never Recycled

Finally, we arrive at the plastics that are almost never welcome in curbside bins. These materials are recycling's biggest headaches due to their chemical makeup, low value, or risk of contamination.

-

#3 PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride): Found in things like pipes and siding, PVC is a durable plastic but contains chlorine. When it's heated during the recycling process, it can release dangerous toxins called dioxins, making it a hazard and a major contaminant for other plastics.

-

#6 PS (Polystyrene): You probably know this material by its brand name: Styrofoam. It’s used for disposable coffee cups, takeout clamshells, and those pesky packing peanuts. The problem? It’s about 95% air. This makes it incredibly light and bulky, so it costs far more to transport and process than it's worth.

-

#7 Other: This is the junk drawer of plastics. It's a catch-all for everything that doesn't fit into the first six categories, including newer bioplastics, tough polycarbonate (used in 5-gallon water jugs), or items made of mixed layers of plastic. Since it’s a random assortment, there's no reliable way to sort and recycle it.

Why Some Plastics Get Recycled and Others Don't

It’s a familiar ritual for anyone trying to do their part for the planet. You rinse out a plastic container, flip it over to find the little chasing-arrows symbol, and toss it into the recycling bin, feeling like you’ve done a good thing. But here’s the hard truth: that symbol doesn’t actually mean it will be recycled.

The real fate of that container has almost nothing to do with good intentions and everything to do with cold, hard economics.

Think of recycling facilities as businesses, because that’s exactly what they are. They operate on razor-thin margins and need to turn a profit to keep the lights on. Just like a grocery store stocks products that people want to buy, a recycling center can only process materials they can actually sell to someone else.

This is the fundamental reason a clear water bottle (PET #1) or a milk jug (HDPE #2) almost always gets a second life, while a flimsy takeout container (Polystyrene #6) is often destined for the landfill. There’s a huge, reliable market for recycled #1 and #2 plastics, but the market for many others is weak or nonexistent.

The Market Dictates Everything

The entire recycling system hinges on simple supply and demand. For a plastic to be truly recyclable in practice, there has to be an end-market—a manufacturer who wants to buy big, compressed bales of it to melt down and create new products.

-

High-Value Plastics: You can think of PET (#1) and HDPE (#2) as the blue-chip stocks of the recycling world. They are relatively easy for sorting machines to identify, their quality is consistent, and manufacturers are always looking to buy them for new bottles, packaging, and even fleece jackets.

-

Low-Value or Negative-Value Plastics: On the flip side, materials like Polystyrene (#6) and the catch-all "Other" (#7) category are often more trouble than they're worth. They can be tough to sort, frequently contaminated with food, and ultimately cost the facility more to process than they can sell them for. They literally lose money on them.

Food residue and other gunk—what the industry calls contamination—throws another wrench in the works. A half-empty jar of peanut butter or a greasy pizza box tossed in with clean plastics can ruin the whole batch. That contaminated bale becomes worthless and gets rejected, ending up in the landfill. This is precisely why the "clean and dry" rule is so non-negotiable.

A Look at The Global Numbers

These economic hurdles are starkly reflected in the global data. In 2022, the world generated around 267.68 million tonnes of plastic waste. Of that staggering amount, only a tiny fraction—roughly 9% of total production—was actually recycled into new goods.

The rest was incinerated or buried in landfills. And within that small 9% sliver, plastics #1 and #2 made up the overwhelming majority. You can dig deeper into these global plastic waste statistics to get the full picture of the challenge we face.

The core issue isn't technological; it's financial. A plastic's journey doesn't end when you put it in the bin—it only begins. If there's no profitable next step for that material, the journey will almost always end in a landfill.

Once you grasp this economic reality, the confusing world of recycling starts to make more sense. It explains why the rules change from one town to the next and why focusing your efforts on recycling the high-value stuff—like clean PET bottles and HDPE jugs—is what makes the biggest, most direct impact.

How Your Location Dictates What Gets Recycled

Ever moved to a new town and felt like you had to relearn recycling from scratch? What was perfectly acceptable in your old curbside bin is suddenly considered trash in your new one. This isn't just an odd quirk; it's the core reality of how recycling works. At its heart, recycling is a hyper-local business, and where you live is the single biggest factor determining what you can and can't recycle.

Think of it this way: every town’s recycling program is like its own small business. Each one operates with a different budget, uses different machinery, and has different buyers for the materials it collects. A city with a shiny new sorting facility might be able to easily handle #5 plastics (like yogurt cups) because its advanced optical sorters can pick them out efficiently. But the town right next door, with older equipment, might not have that capability. For them, those same yogurt cups are just trash.

Distance is another huge factor. If your community is hundreds of miles from a plant that actually buys and processes a certain type of plastic, the cost of shipping it there might be too high to make it worthwhile. It's simple economics, and it often means that perfectly recyclable material ends up in a landfill.

The Confusing Patchwork of Rules

This all creates a dizzying patchwork of regulations that can change dramatically from one zip code to the next. The rules aren't based on what is technically recyclable, but on what is logistically and financially possible for your specific town at this very moment.

These local limitations have a massive effect on national recycling rates. In the United States, a huge producer of plastic waste, the plastic recycling rate has hovered around a dismal 5% in recent years. This was heavily impacted by major global shifts, like China’s 2018 ban on most plastic waste imports, which essentially left many U.S. towns with no one to sell their materials to.

Contrast that with the European Union, which manages to recycle about 41% of its plastic packaging, in large part because of more standardized regulations and investments in infrastructure. You can dig deeper into these global recycling disparities to see just how differently countries handle their waste.

Why You Must Check Your Local Rules

Because the system is so fragmented, tossing something in the bin and just hoping it gets recycled—a habit known as "wishcycling"—often does more harm than good. It can contaminate an entire batch of otherwise good materials, drive up costs for your local program, and even cause machinery to break down.

The single most important thing you can do is to stop guessing and start checking. The only reliable source of truth is your local municipality or waste management company's website.

Taking a minute to look it up is what separates good intentions from real impact. It ensures your efforts aren't wasted and gives the items you carefully rinse and sort the best possible chance of actually becoming something new.

Avoiding Common Mistakes That Contaminate Recycling

Knowing your plastic resin codes is a great first step, but it's only half the battle. Even with the best intentions, a few simple missteps can contaminate an entire batch of recyclables, forcing perfectly good material to be sent straight to the landfill. This is where a lot of our collective effort, unfortunately, goes to waste.

Think of the recycling stream like a very sensitive recipe—one wrong ingredient can ruin the whole thing. A single greasy takeout container or a few flimsy plastic bags can jam up the machinery and bring the whole sorting process to a grinding halt. To be truly effective, we have to move beyond "wishcycling"—tossing something in the bin and just hoping it's recyclable—and learn how to prepare our plastics the right way.

It doesn’t take much effort, but doing it right ensures the materials you toss in the bin actually have a fighting chance of being reborn as something new.

The Problem With Food Residue

If there's one public enemy number one for plastic recycling, it’s food contamination. That little bit of leftover peanut butter in the jar, the ketchup film in the squeeze bottle, or even the last drops of soda can ruin a massive bale of plastics.

When these items get to the facility, they're compressed into huge, dense bales for transport. Any food residue left inside gets squeezed out, attracting pests, growing mold, and generally creating a mess. No manufacturer wants to buy that. A greasy jar isn't just one rejected item; it can spoil an entire bale of otherwise clean plastics, rendering it worthless.

The rule of thumb is simple: clean and dry. A quick rinse is usually all you need to remove most food waste. Scrape out anything thick like yogurt or peanut butter, give it a quick wash, and let it air dry before it goes in the bin.

Taking thirty seconds to do this dramatically increases the odds that your plastic will actually complete its recycling journey.

Beware of "Tanglers" in The Machinery

Another huge headache for recycling facilities are items that tangle up in their complex sorting machinery. They even have a name for them: "tanglers." And they're a costly nightmare for the people who have to deal with them.

The most common culprits are things you probably handle every day:

- Plastic Bags: These are the absolute worst. Grocery bags, bread bags, and other thin films get wrapped so tightly around the spinning gears of sorting equipment that workers have to shut the whole system down and cut them out by hand. Never put these in your curbside bin.

- Plastic Film and Wrap: Just like bags, that shrink wrap from a case of water bottles or a sheet of bubble wrap will cause the exact same tangling issues.

- Loose Bottle Caps: On their own, small caps are too tiny to be sorted properly and often fall through the cracks in the machinery, ending up in the trash. The best practice these days is to empty the bottle, give it a good crush to get the air out, and then screw the cap back on. That way, it gets recycled along with the bottle it belongs to.

Just because these items don't belong in your mixed recycling bin doesn't mean they're trash. Many grocery stores and big-box retailers have special collection bins right at the front entrance specifically for plastic bags and films.

Small Items Cause Big Problems

Finally, when it comes to recycling, size really does matter. Most sorting facilities are built to handle items of a certain minimum size—think anything larger than a credit card.

Tiny plastic items just can't be processed correctly. Things like straws, coffee pods, and plastic cutlery are almost guaranteed to fall through the screens and conveyor belts. They slip through the system and end up mixed in with all the other non-recyclable junk destined for the landfill.

The only real solution for these small items is to avoid them from the start by choosing reusable alternatives whenever you can.

Putting It All into Practice: Simple Steps for Smarter Recycling

Knowing the difference between resin codes is a great start, but real change happens when we turn that knowledge into consistent habits. It’s not about getting it perfect every single time. It’s about building a few simple routines that make a massive difference in keeping our recycling stream clean and effective.

The idea is to stop "wishcycling"—tossing something in the bin and just hoping it gets recycled—and start recycling with confidence. This way, you know your efforts count and the materials you sort have the best shot at a second life.

Your Simple Recycling Checklist

Getting into the groove is easier than you think. Forget the guesswork and just follow this simple, three-step process for every plastic item that comes through your door.

-

Always Check Your Local Rules First. This is the golden rule. Before you even think about rinsing a container, find out if your local program actually accepts that specific plastic number. Bookmark your town’s or city’s recycling website on your phone so the info is always just a tap away. Guidelines can and do change, so it never hurts to double-check.

-

Embrace the "Clean and Dry" Mantra. Leftover food and liquids are the biggest recycling contaminants. Scrape out any gunk, give the container a quick rinse to get the residue off, and let it dry. A clean item is a valuable commodity for recyclers.

-

Keep Special Plastics Separate. Those flimsy plastic grocery bags, bubble wrap, and other soft films (usually #4 LDPE) are notorious for tangling up recycling machinery. They should never go in your curbside bin. Instead, bundle them together and bring them to a retail store drop-off point on your next errand run.

One of the most common recycling mistakes is treating all plastics the same. By separating the hard plastics your curbside program wants from the soft films that need to be dropped off, you help prevent contamination and equipment shutdowns. It makes the whole system run smoother.

Making these small adjustments part of your daily routine is what moves the needle. You won’t just be increasing the odds that your own plastics get recycled—you’ll be helping your local recycling facility do its job better for everyone.

Your Top Plastic Recycling Questions, Answered

Let's face it, standing over the recycling bin can sometimes feel like a pop quiz. You're trying to do the right thing, but the rules can be confusing. Here are some quick, clear answers to the questions we hear most often.

Should I Leave the Caps On or Off My Plastic Bottles?

This is a big one, and the advice has changed over the years, which is where a lot of the confusion comes from. For a long time, the rule was "caps off." Not anymore.

These days, most modern recycling facilities actually want you to screw the caps back on the empty bottle. Their sorting technology has gotten good enough to handle it. Leaving the cap on ensures that small piece of plastic makes it through the system instead of falling through the cracks in the machinery and ending up in a landfill. Just be sure to empty the bottle first!

Can I Recycle Bioplastics or "Compostable" Plastics?

In a word: no. This is a really important one to get right. Tossing a "compostable" plastic container into your recycling bin is a major contamination problem.

These materials, like PLA, are designed to break down in a high-heat industrial composting facility. They are not meant to be melted down and reformed like traditional petroleum-based plastics.

Think of it like trying to bake a cake with salt instead of sugar. Bioplastics look similar, but they are chemically completely different. When they get mixed in with a batch of regular PET or HDPE, they can ruin the entire melt, forcing the facility to send tons of otherwise good material to the landfill.

Always keep bioplastics out of your recycling bin.

What's the Big Deal with Black Plastic?

The problem with black plastic isn't the plastic itself—it's the color. Recycling plants rely on high-tech infrared (IR) optical scanners to identify and sort different types of plastic as they fly by on a conveyor belt.

The carbon black pigment used to make plastic black absorbs that infrared light. To the machine, it's like the item is wearing an invisibility cloak. The scanner can't see it, so it can't sort it. As a result, that perfectly good (and often valuable) plastic gets rejected and sent to the landfill.

Ready to clear your kitchen of single-use plastics for good? At Naked Pantry, we deliver delicious, organic pantry staples in 100% plastic-free packaging. Start building your zero-waste pantry today.